March is women’s history month, and in the spirit of that we’ve been highlighting groundbreaking and notable female characters in railroad history on our various social media platforms. In this post, we’ll wrap up the month by expanding upon the stories of some of these women, as well as introduce a few new faces. Here’s to women in the past, the present and the future.

|

| Anna Judah |

Anna Judah (1828-1895) - Unfortunately, we don’t know much about Anna, because her husband Theodore Judah is the one who made news, although Anna was by his side for his biggest accomplishments. Theodore Judah was one of many men working to build the Sacramento Valley Line, but he and Anna dreamed of something bigger: a railroad that would stretch all the way to the Pacific. Theodore planted the seed of this idea at the 1859 Pacific Railroad Convention, but he had no prospective route for his railroad. The issue with trying to build a railroad line to the Pacific is having to go over the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range – these massive craggy peaks span over 250 miles on the eastern side of the state of California, conveniently blocking the way to the other side of the c |

| Theodore Judah |

ountry. To build a rail line over the mountains, Theodore Judah would have to scout them. In 1860 Theodore Judah was offered a chance to cross Donner Pass with a storeowner named Doc Strong from the small town of Dutch Flat California. Anna, who was a talented artist, purchased herself a pair of trousers, a set of gaiters and set out to follow her husband into the wilderness in the summer of 1861, capturing the scenery of Donner Pass with watercolor and oil paints. Donner Pass, despite its sordid history, proved to be the perfect place for a railroad. It provided a slow gradual rise that would be easy for a steam engine to climb, as well as an easy descent following the Truckee River. Compared to the other peaks of the Sierra Nevada, which are craggy and double ridged, Donner Pass was the clear option for the route to be placed. In October of 1861 Theodore and Anna left the mountains with financial support and a 90-foot map of the prospective route. On July 1st, 1862, The Pacific Railroad Act was signed by President Abraham Lincoln and construction began. Unfortunately, Theo never got to see his dream achieved as he died of yellow fever in New York in late 1863. Anna though, saw the railroad built to completion. The Pacific Railroad the Judah’s had dreamt of was completed on May 10th, 1869, the couples wedding anniversary.

|

| Dr. Mary Pennington |

Mary E. Pennington (1872-1952) - Dr. Mary Engle Pennington is one of the best historical examples of a lifelong academic. She began her education at the University of Pennsylvania in 1890, a time in history where a woman pursuing higher education was relatively unheard of. The University of Pennsylvania didn’t offer degrees to women at the time, but Mary earned numerous ‘proficiency certificates’ in subjects ranging from chemistry, zoology, and botany. Her high grades and numerous accolades impressed the University of Pennsylvania’s Board of Trustees enough that despite her sex, she was granted an advance PhD in 1895. Earning a PhD wasn’t enough for Mary though, so she packed up and headed to Yale. From 1897-1899 Mary does research in physiological chemistry and does work as a bacteriologist with the Philadelphia Bureau of Health and the Pennsylvania Department of Health (her work with both of these government agencies subsequently raises the sanitation standards for the handling of milk and other various dairy products.). In 1905, Mary catches the eye of Dr. Harvey Wiley, who at the time was the head of the US Department of Agriculture. Dr. Wiley offers Mary a position on his newly formed ‘Poison Squad’, a group of like-minded talented chemists and botanists that believed consumers should know what goes into the food they were purchasing. The work of the Poison Squad directly led to the 1905 passing of the Pure Food and Drug Act, which required manufacturers to list ingredients clearly on the packaging of their products. Shortly after the passing of the act, Mary is asked by Dr. Wiley to head The Bureau of Chemistry’s Food Research Lab, despite all of Mary’s qualifications and experience, the two ran into a roadblock. Mary was a woman, and Dr. Wiley was worried that a woman in such a high-ranking position would upset people, so the pair found a loophole. Dr. Wiley submitted Mary’s resume and credentials under the name M. E. Pennington, and never explicitly used female pronouns for her, and she was hired almost immediately. With her shiny new job position Mary began conducting pioneering research in cold storage and refrigeration. On October 3, 1908, Mary presented to the Warehouseman’s Association in Washington D.C, as part of her presentation a brand-new cold storage box car was displayed. Now in this point in time cold storage cars or ‘reefer’ cars (short for refrigeration) were common. The first reefer cars from the 1860s consisted of metal racks from which beef and pork could be hung over a mixture of rock salt and ice. This design was vaguely improved upon in 1875, making use of blocks of ice packed between sawdust and hay as insulation and adding hatches in the roof to provide air circulation within the car. Dr. Pennington thought that this could be greatly improved upon, she had a small railcar be turned into a travelling laboratory that would be attached to the back of a railcar, allowing Mary to conduct various experiments. |

| Dr. Pennington Conducting Experiments on top of a boxcar |

She concluded that the layers of insulation were much too thin, there wasn’t enough air circulation (low circulation could lead to the possibility of molding), and she noted the exterior shells of the cars themselves were prone to cracking open. Utilizing Dr. Pennington’s research, the first modern reefer cars were constructed and had a monumental impact on the economy. The modern reefer all but eliminated the need to transport livestock to and from slaughterhouses. Consumers also enjoyed the benefits; all varieties of fresh fruits and vegetables could now be transported across the country. In fact, The Northwest Railway Museum has a reefer car on display that was used for exactly this purpose, the transport of fresh fruits. Dr. Mary Pennington’s storied career in refrigeration and cold storage (well over 30 years), earned her the nickname ‘Ice Woman’. If you want to know more about her life and career, she has her own chapter in the book Iron Women by Chris Enns is available for purchase in the museum’s bookstore in the Snoqualmie Depot.

|

| Olive Wetzel Dennis |

Olive Wetzel Dennis (1885-1957) - Olive Dennis graduated from Goucher college in 1908 with a Bachelor of Arts degree, and the following year procured a dual master's degree in mathematics and astronomy from Columbia University. She then took a quick break from collecting degrees, and took a job teaching math (teaching was one of the only job options for a well-educated woman in the early 1900s) for 10 years at a vocational school in Washington D.C. And then she decided teaching wasn’t for her. As a child, Olive was fascinated with building things, “While her parents gave her dolls, she was more interested in constructing doll houses and furniture than sewing doll clothes. When she was 10, she built her brother a model streetcar with trolley poles and reversible seats.” (The Baltimore Sun). A 1940 article from The New York Times quotes her as saying “I have always loved making toys and have been trying to do so ever since I could drive a nail”. Following this draw to engineering and construction, Olive began her studies at Cornell University in 1919, graduating (incredibly) the next year with her masters in civil engineering, becoming the second woman to ever receive the degree. She was hired by the Baltimore and Ohio Railway as a draftsman for bridges, quickly rising through the ranks and earning the title of service engineer and being tasked with making rail travel as comfortable as possible for the passenger. Dennis recalls in a 1947 issue of the Baltimore Sun that she “was told to get ideas that would make women want to travel on our line,”. Which was a good idea, a really good one. The B+O was having a hard time retaining passenger numbers with the rising quantity of cars and busses, and they figured if the working man’s wife wanted to ride on the train, if she saw it comfortable enough to be considered the superior option – the men and the rest would follow her. And so, Olive began her work improving the comfort of passenger cars, she would ride back and forth (travelling almost half a million miles during her career) and identify problems along the way. She found the seats to be uncomfortable, so she promptly added armrests, footrests, head covers, dimmable ceiling lights and made it so you could recline the seat like an armchair. She found that there was a major issue with the climate control within the cars: if you needed some air your only option was to open a window, which would promptly allow for the steam engines' plume of soot and smoke to fly in and create an incredible mess. So, in 1927 she gained a patent for the “Dennis Ventilator” which allowed passengers to control the air flow within the car, essentially an early version of air conditioning (in fact thanks directly to Olive, B+O introduced the world’s first fully air-conditioned train in 1931). When she found the dressing rooms to be a bit cramped, she quickly made them a tad bit roomier, adding paper towels, disposable cups, and liquid soap just for good measure. When businessmen complained of being too tired after a full course filling meal in the dining car, she introduced a-la-carte menus. She even designed the dishes these businessmen would eat on, creating the iconic ‘colonial chinaware’ that featured sights seen along the line and little trains chugging along the edges. She was key in introducing on board nurses and stewardesses, which allowed travelling mothers to feel safe relaxing while on board. Some of her more major improvements included a fully redesigned undercarriage that provided a smoother ride, and conversational ‘club’ cars, allowing for a sense of community among the passengers. But none of these held a candle to her masterpiece, the stunning Cincinnatian P-7d 4-6-2, a massive art deco, silver and blue beauty of a train that could complete the route from Cincinnati to Washington D.C. in under 12 hours. |

| Olive Dennis's Cincinnatian |

All in all, Olive Dennis was a priceless asset to the B+O rail line, making travel more comfortable for everyone involved. As The Baltimore Sun, her hometown newspaper, put it years after her death “She took the pain out of the train”

|

| Rosina Corrothers Tucker |

Rosina Corrothers-Tucker (1881-1987) - Rosina Corrothers Tucker had been married before, it’s where the ‘Corrothers’ part of her name came from, but she probably didn’t realize how revolutionary her second marriage would become. Berthea Tucker, Rosina’s second husband worked as one of many Pullman Porters, a fleet of black workers that served customers on board industrialist George Pullman’s luxurious passenger coaches. Starting out as freed slaves who would work for cheap, the job of a porter quickly became a point of pride for many workers – here were black men who frequently brushed shoulders with the white elite, even if those white elite tried their hardest to not acknowledge them. Despite slavery being abolished, racism was far from it. Pullman Porters were treated horribly despite being valuable company assets, “As Lawrence Tye writes for the Alicia Patterson Foundation, at some point porters began to be addressed by their employer’s first name, just as a slave would be addressed by his master’s name before emancipation. This humiliation was heightened by the seemingly endless job description porters were expected to fulfill.” (Smithsonian Magazine). The men were not allowed breaks aside from using the restroom, they were not allowed to sleep during shift while their white counterparts had their own break areas and sleeping cars for use during longer shifts. Porters were expected to shine shoes, make beds, carry luggage, all while remaining ‘invisible’ to the white passengers they served. They were valets, security guards, and bellhops working seemingly endless hours and earning nothing near a living wage. Rosina became witness to this mistreatment firsthand when she married Berthea, and she was also looped into the ongoing efforts of the Porters and their families to organize a union. The need for workers’ rights, for a union was obvious to her, but the organization just wasn’t there. Rosina knew that if a Porter’s union was ever going to work, they were going to need help. In 1925, with the help of Tucker and others, they looped in labor organizer and civil rights activist Asa Philip Randolph and successfully formed the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Rosina played an instrumental part in the union's organization, she collected union dues, and helped to keep the working Porters and their families informed as the union continued to grow. “The Pullman Company closely monitored employees' activities and punished those who supported the union. The BCSP suspected that women would be subject to less scrutiny than men. As a result, it was often the family members of porters or women employed by the Company who carried out home visits or shared literature about the union.” (National Parks Service) In 1937, the union was successful in securing raised wages and lowered hours, making working as a Pullman Porter significantly more bearable. This win for the union cemented The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters as the first successful labor union for black workers. Rosina continued to play a monumental part in the fight for black railroad workers rights, she later founded the D.C. women’s auxiliary of the Brotherhood. Rosina went on to live 105 years, passing away in 1987.

|

| Arcola Philpott |

Arcola Philpott (1913-1991) - Arcola Philpott suffers from the same problem as Anna Judah, despite widespread acknowledgement of her importance to the causes of both women and black workers, information about her and her actual work is incredibly hard to track down. Here’s what we do know about Arcola, she was an accomplished pianist and could speak several languages, and she was the first black woman to ever serve on the Los Angeles Railroad’s interurban system. She was hired on August 1, 1944, and she opened the door for 6 other black motormen, who were hired just weeks after she was. Arcola’s daughter Ethel Philpott credits her for inspiring many women to enter fields that were historically male dominated, “My mother was just like that, born in the wrong era for all the things she wanted to do; she was a real go-getter. She was extremely intelligent, courageous, fearless and a life-long learner.” (Ethel Philpott to Metro LA). After working her revolutionary position with the LA Railroad, Arcola moved to Chicago, where she did work as a nurse, and later a Researcher for the University of Chicago’s History Department.

|

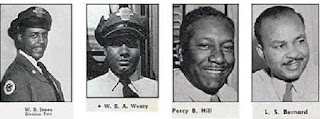

| Some of the black motormen hired after Arcola |

Railroading is a male dominated career; it always has been. But that doesn’t mean that can’t change, women are making their presence known in hundreds of different careers, and railroading is no exception. Take Edwina Justus, another woman featured on our social media. Edwina was the first black woman to work as an engineer for the Union Pacific Railroad Company. And Jolene Molitoris, a more recent addition to the list of history making women working for the railroads, the first woman to be appointed head of the Federal Railroad Administration. Powerful and influential women have always been a part of history, whether it be in the background, providing support for their husbands and helping them make history, or at the forefront of innovation, keeping our food fresh and our bodies comfortable.